Uncertainty breeds hesitation — and a cloudy economic and remote-work environment continues to obscure a clear path to recovery for the U.S. office sector. Leasing activity remains subdued as employment and office-usage expansion plans are put on hold until more clarity emerges.

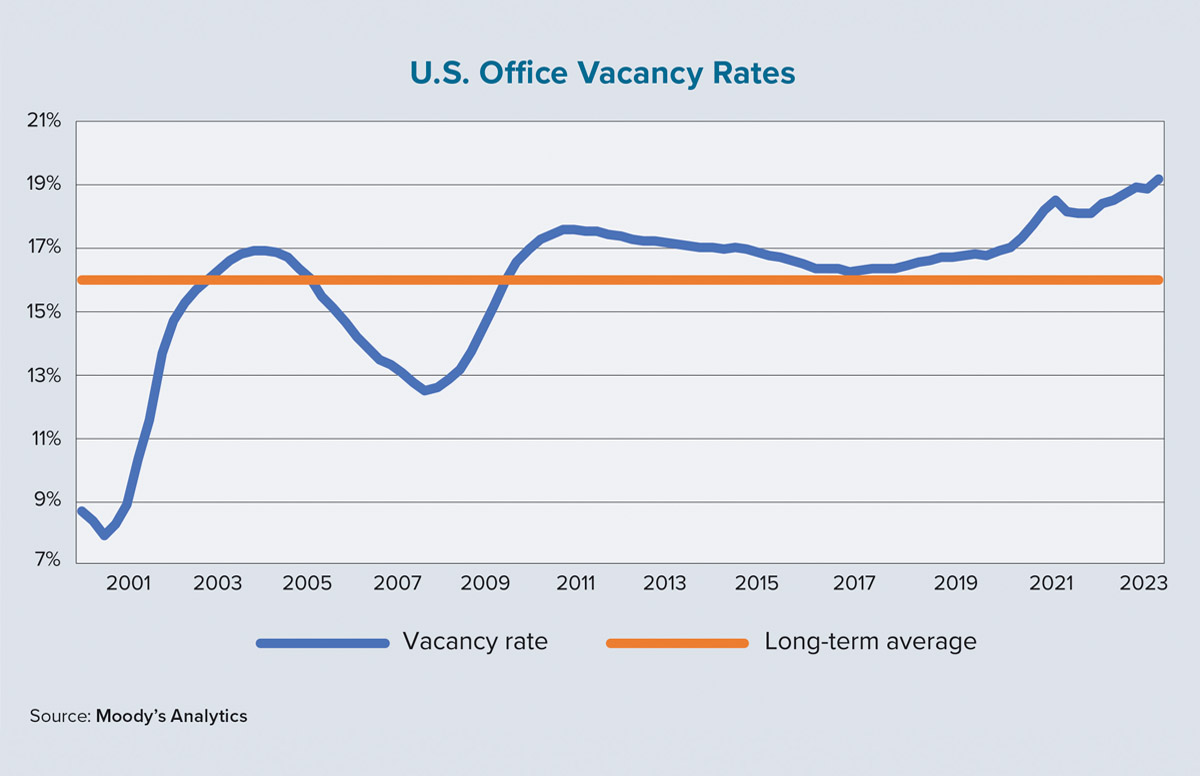

In the third quarter of this year, net absorption across the sector was strongly negative, with the total amount of leased square footage declining by 12.4 million square feet at the national level. This was the largest decline in the Moody’s Analytics dataset since early 2021. Furthermore, as the chart on this page shows, the current vacancy rate has reached 19.2%, the highest level since the tail end of the savings and loan crisis in the early 1990s. We expect this bumpy ride to result in another increase of 20 to 40 basis points (bps) over the next 12 to 18 months.

On the surface, this is a sour story, with data and anecdotes likely to confirm many pundits’ expectations of an apocalypse for the office sector. And while it’s easy to concede this as one of the most challenging moments in the history of the office property type, it’s also important to recognize the depth and nuance of a story that actually began many years prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What is this story? Well, it’s more of an epic than a tale, with an overarching theme of obsolescence and change. The pandemic served to accelerate the demand shift toward newer and more flexible spaces for the country’s massive and growing knowledge-based economy, but this evolution actually started long ago.

There are a few facts to ponder. First, the decline in leased office space in third-quarter 2023 (the aforementioned 12.4 million square feet) is only about one-third the amount of the worst quarterly decline recorded during the financial crisis of the late 2000s. Second, as shown on the chart above, the vacancy delta during the Great Recession was a massive 500 bps, whereas the post-pandemic change is about 200 bps.

Third, the most intriguing and telling fact may be that during the expansionary period of 2010 to 2019, the national office vacancy rate retreated by only 130 bps from its peak before floundering at a level above its long-run average of 16% — until the pandemic arrived. Given that construction activity during this expansion was modest at best, this is evidence of an attitude shift and evolution for the office market that began long ago.

Languishing national-level property values confirm this market sluggishness. Gains in office values from 2010 to 2019 amounted to about 50% of the commercial real estate market as a whole during this decade. But it’s also worth noting that not all properties are faring equally.

Akin to the retail sector of the past three decades, we are seeing successful office properties built between 1960 and 2000 make way for a modern standard in urban or suburban locations that have become more en vogue. Well-placed new construction has leased up reasonably well as tenants have been willing and able to move into these spaces for more than a decade.

The current flux in the office market is simply serving to update the timeline for changes that have been in the works for quite a while. This is not an end to the office, but it is a fundamental change in the locations of power and buildings within each city.

It’s expected that successful office buildings of the future will be those in mixed-use areas that much more closely resemble “24-hour neighborhoods” rather than the “9-to-5 neighborhoods” of the 1980s. Distinct zones of office activity are quickly dying and are being replaced by areas where office, retail, residential and public spaces can mingle and thrive together. Employees will come back to the office, but it will take both a high-quality building and a high-quality location to do that. ●

Author

-

Thomas LaSalvia, Ph.D., is head of commercial real estate economics at Moody’s Analytics CRE. He has extensive experience in space and capital-market analysis, with specific expertise in optimal location theory.